I’m curious as to what comes to mind when someone with a non-clinical background hears the phrase “social skills.” As a therapist with a strong background in behavior modification, I’m familiar with social skills – what they are, why they’re important, how to teach them, how to reinforce them.

So what are social skills? They’re the things (skills) we do to socialize with other people. These skills can be both verbal and non-verbal, and are important for humans to learn in order to be successful building relationships with others. How do we learn social skills? Many times, we learn them through watching others and mimicking their behavior. This is such a great, mostly effort-free way for your kids to learn prosocial skills. But guess what? Kids can also learn inappropriate, negative skills from other kids (and adults!). So it can be helpful for parents to practice these skills with kids – especially those skills that you see your child needs some improvement in.

Some individual social skills include: take turns, respecting boundaries, sharing, asking for help, asking permission, saying “thank you,” saying “sorry,” waiting patiently, following directions, complimenting others, accepting “no” for an answer, resisting peer pressure, greeting others, and saying “no” to others appropriately. This is not an exclusive list by any means. There are many, many more social skills. The blog site And Next Comes L, has a list of 50 social skills, which you can find here on their site.

Why are social skills important? The “big picture” answer is to successfully build relationships with other people. Social skills are how we meet and keep friends. Social skills are how we maintain bonds with family members. Social skills help with interviews, getting jobs, and keeping jobs. Social skills are how we sell items or ideas to other people. Pretty important!

How to teach them? Yes, your children will be exposed to these skills by watching others and may mimic these skills. If you notice your child struggling with a social skills, you can model the skills for them and practice. Then you can reinforce this with praise when you see them do it well (both in practice and outside of it).

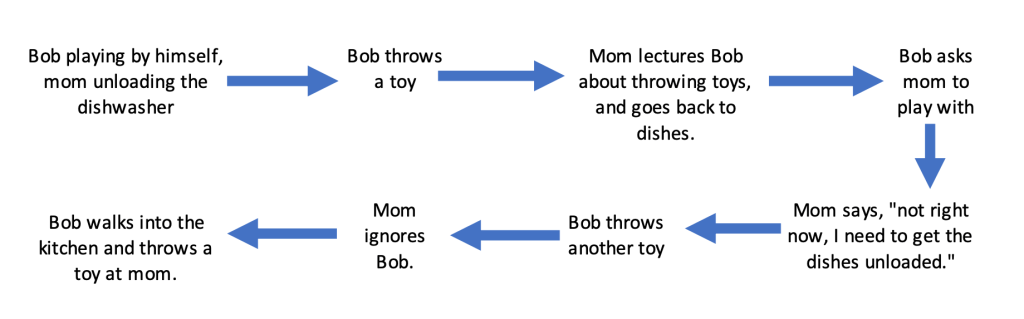

What happens if we don’t teach/practice them? We may end up with children who struggle to interact positively with others. As a therapist, I see this in some of my clients. As a parent, I see this in my own kiddo and in other kiddos we interact with. I see my daughter struggle to be a good sport when she loses a game. I see many kids struggle to take turns and wait patiently while playing at playgrounds. I see clients who struggle to show gratitude, which leaves family members feeling resentful. I see clients who have “perfectionist” tendencies struggle to ask for help when they need it.

Now, please hear me out when I say that no child will be “perfect” with social skills. I’m not of the opinion that all parents should be practicing all of these skills with their kids – we have enough to do! There’s no need for alarm if your child is still learning. Maybe they just need a little more time, socializing, and developmental progress to really nail those social skills. But if you see them struggling and it’s affecting their relationships with others, it’s a great idea to practice with them. This series is not to add to the parent load by preaching about ANOTHER thing you must do with your children. This is an informational series for parents who may see their child struggling in an area or two and want to help.

Be on the lookout for posts about individual social skills to be added! I hope to cover each social skill listed in this post. I can’t wait to hear how you’re practicing these skills with your kiddo!

Disclaimer: I am a licensed mental health therapist, but I am not your therapist. The information in this article is for general informational purposes only. This article does not create a therapist-client relationship. If you need specific recommendations based on your individual circumstances, please consult with a mental health practitioner near you.