Most parents think their child would never do anything bad enough at school to get sent home, but it happens. Kids have rough days too. You may not be overly concerned if it’s a one-time occurrence, but unfortunately, it can snowball fairly quickly. Why? Because most kids would rather be at home than at school!

I don’t want to bash schools – I know their options are fairly limited, but oftentimes sending a child home for negative behavior can turn a small problem into a big one. Let’s look at what can (not always!) happen when a child is sent home from school for negative behavior. The child learns that they can go home as long as they do something “bad” enough at school – being sent home is a reward. So the child will continue acting up so that he/she can be sent home. Then, once the school starts developing a behavior plan (IEP) in an attempt to try other interventions and prevent the child from being sent home, it’s too late! Now the child will do whatever it takes to be sent home, even if it means resorting to behaviors more severe than when they first got sent home (this is called extinction burst).

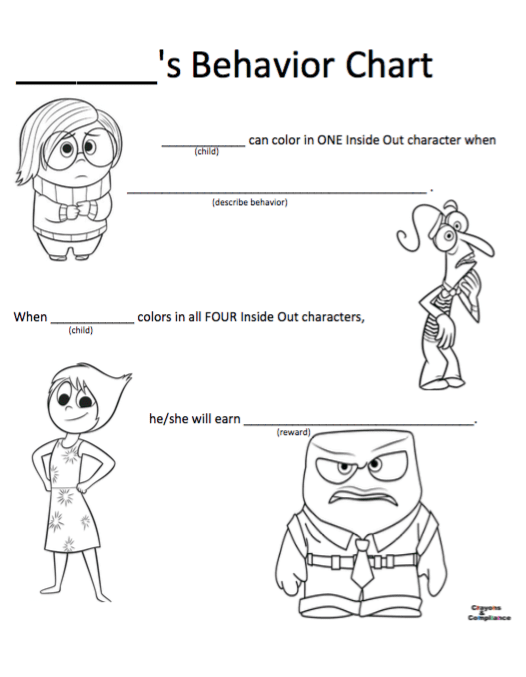

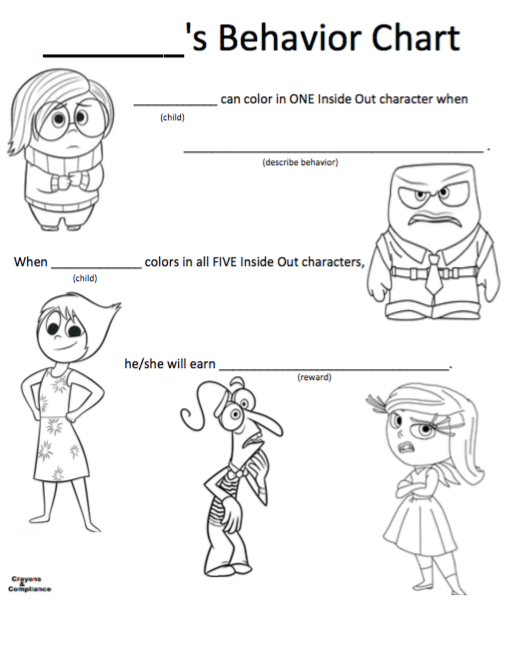

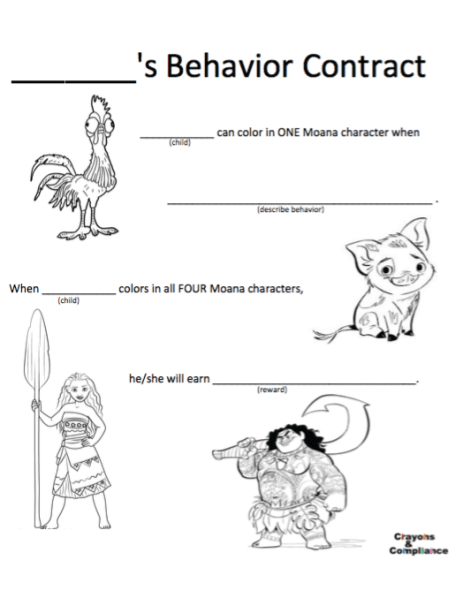

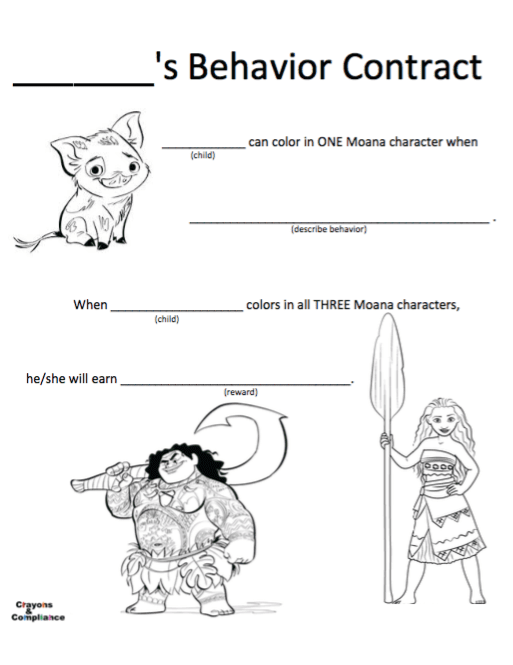

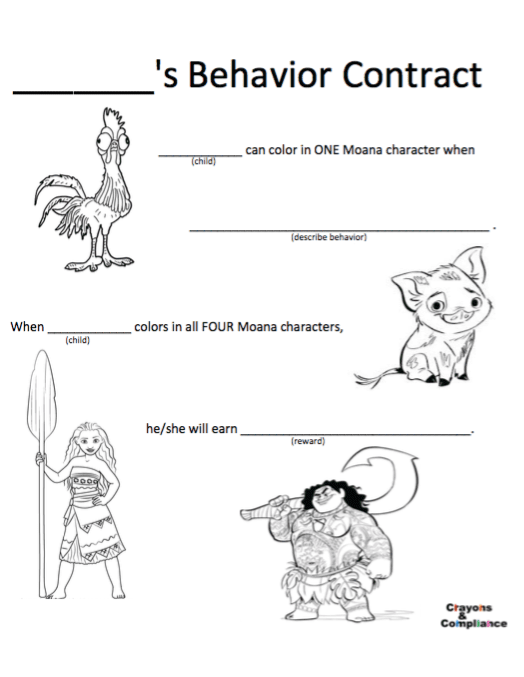

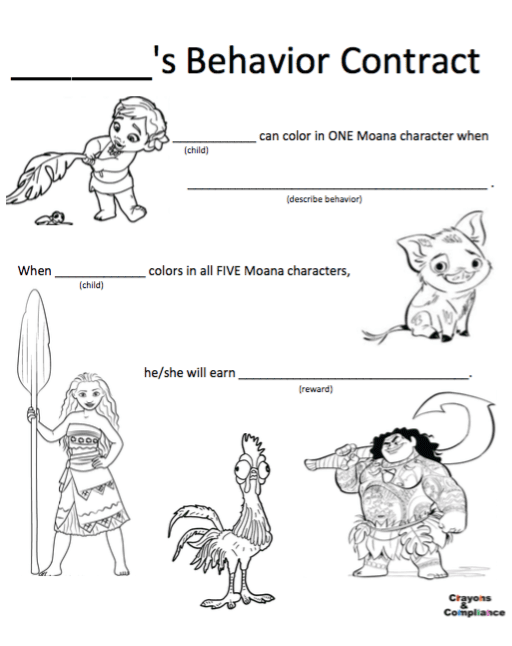

Unfortunately, there aren’t a lot of things that parents can do about school behavior and the school’s response. Parents can use rewards and negative consequence (click here for tips on how to do so). Parents can also do their part to reduce the likelihood that being sent home is reinforcing for a child. So what do you need to do in order to make sure going home isn’t like a reward?

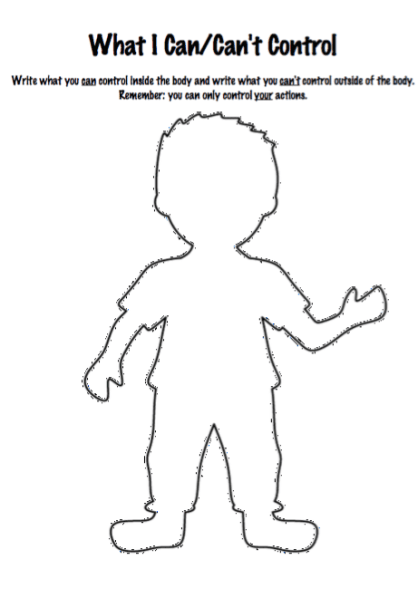

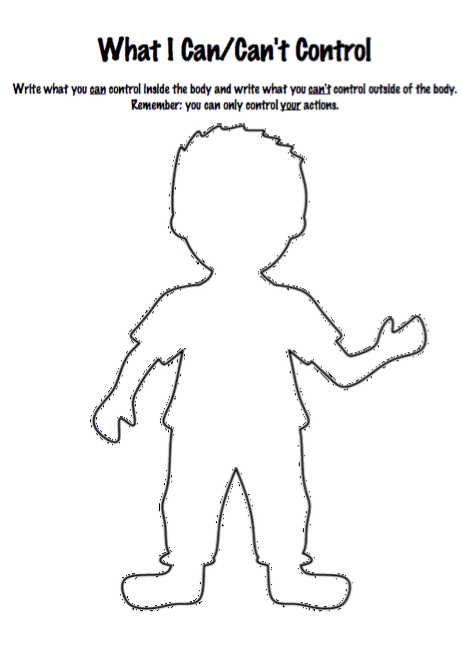

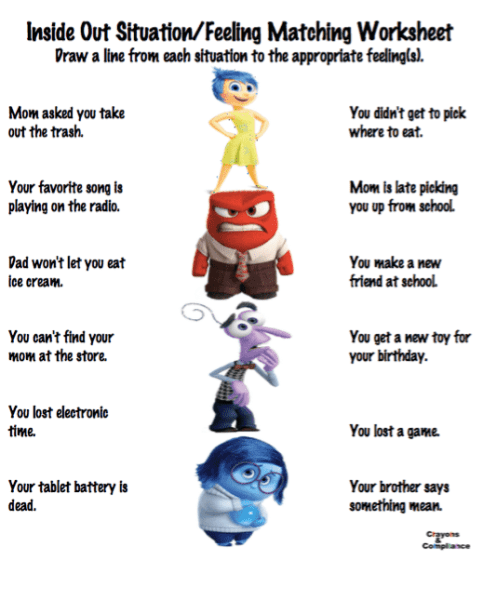

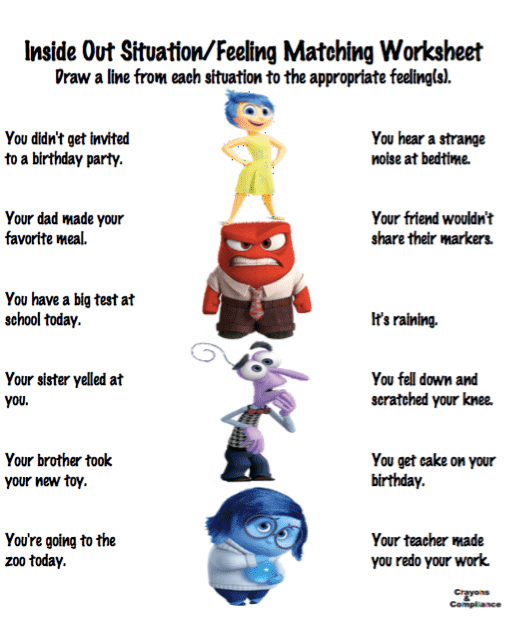

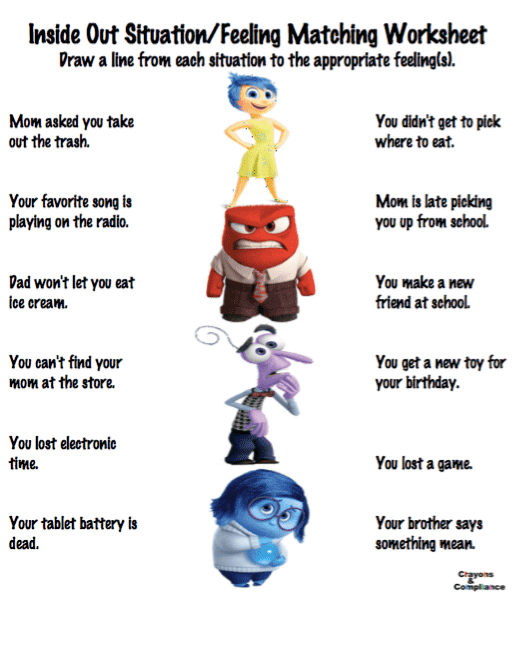

- Make sure your child doesn’t get a free pass to have fun the rest of the day. Don’t let them spend the whole day in their room playing with their favorite toys. Don’t take them on fun errands or to the park. Make sure that they’re doing something that they don’t necessarily like during the time they’re supposed to be in school. Let me be clear… I don’t mean stick your kiddo in a corner for 5 hours. But consider having your child do some chores or do school work (or print out some academic worksheets).

- Make sure you’re not giving your child an excessive amount of attention for what happened (remember that bad attention can still be reinforcing). Sure, you’re probably going to talk to your child about what happened and what a better choice would’ve been. Here’s what you don’t want to happen… your child gets attention from you as you discuss the situation the entire way home, then more attention when you call his grandparent and tell them what happened, then even more attention while hearing you talk to your spouse when they get home from work, and then they get even more attention when their other parent comes to talk to them about what happened. Cut that attention down as much as you can if you have a child who thrives on being the center of attention (give them that attention when they do something well instead!).