I’m taking a break from the Social Skills Series to write about Reinforcement. My post Crash Course on the Four Functions of Behavior is one of my most popular. What this tells me, is that people are actually interested in these terms/theories, and looking for more information. So if you are looking for more information on what Reinforcement is, this post is for you.

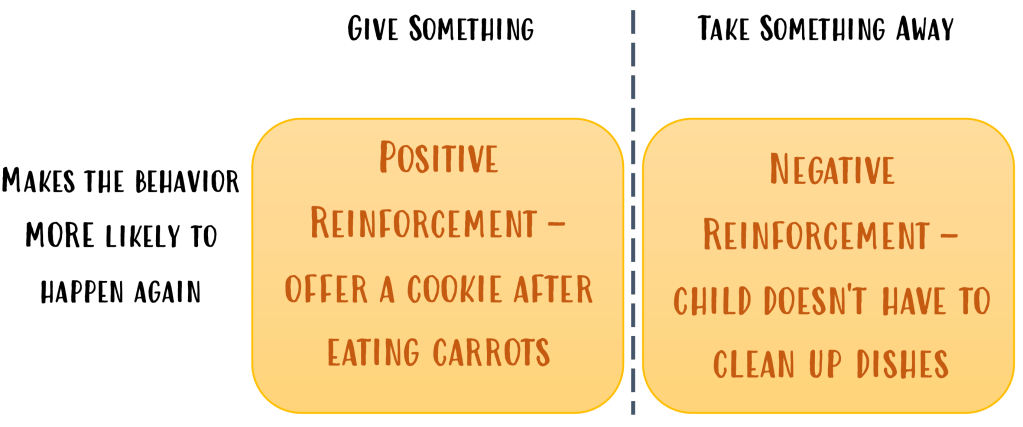

So what is Reinforcement? Reinforcement is anything that makes it MORE likely for a behavior to happen. Or, if you prefer dictionary definitions, Merriam-Webster says that Reinforcement is, “the action of strengthening or encouraging something.” In the behavior modification world, the “thing” you are trying to strengthen or encourage is positive behaviors. Check out the chart below (AND/OR download it here) – in this post we’re focusing on the top two boxes – positive and negative reinforcement. As you can see, you are either taking something (unpleasant) away or giving something pleasant in order to make the behavior more likely to happen.

There are a multitude of actions/things that can be used as Reinforcement. Reinforcement can be negative OR positive, and this is where it gets a little tricky. “Negative” in “negative reinforcement” doesn’t mean that it’s a punishment. Both negative and positive reinforcement are “good” things that make a behavior more likely to occur. They are both reinforcing. Let me say it again:

Both positive reinforcement AND negative reinforcement are “good” – BOTH make a behavior more likely to occur again.

Positive Reinforcement is usually easier to understand because it’s giving something good to make it likely the good behavior will reoccur. Think praise, rewards, and positive attention. My child does something “good” that I want them to do again (like cleaning up her socks off the floor, so I give her an extra cookie. Or she is kind to a friend, so I tell her what a great job she did. Or she says “okay” with no whining when I say it’s time to turn off the tv, so I give her 5 minutes of tablet time. Or she gets ready for bed without a fuss, so I read an extra book with her before bed. All of these are examples of positive reinforcement. You get something good for doing something good, which makes it more likely you’ll keep doing something good.

So what does the “negative” in Negative Reinforcement mean? It means you’re taking away something considered “bad” or unpleasant to make the positive behavior more likely to occur again. The most popular example of this is the alarm for seatbelts. In cars, it’s pretty common for an alarm to ding if you don’t put your seat belt on. That ding is pretty obnoxious. Once you put your seatbelt on, the dinging stops. This is negative reinforcement. You’re taking away something unpleasant (the dinging) to reinforce positive behavior (putting on the seatbelt). You get something unpleasant removed for doing something good, which makes it more likely you’ll keep doing something good.

Here’s an example of how both negative and positive reinforcement may be used to reinforce a good behavior. Let’s say your child doesn’t like carrots and typically whines about them, but today they ate all their carrots without any whining or fussing.

In this scenario, you have the option of giving something good (positive reinforcement) or taking away something “bad” (negative reinforcement) to make it more likely your child will eat their carrots without a fuss next time.

Unfortunately, I think negative reinforcement may be used to reinforce negative/bad/undesired behavior more often than it is to reinforce positive behavior. If you give your child a food they don’t like, then take it away when they whine/scream/complain/yell… that’s negative reinforcement. You are taking away something unpleasant (the yucky food), which reinforces the negative behavior (whining/screaming/complaining/yelling). If you tell your child it’s time to help with a chore, then change your mind when they throw themselves on the floor kicking and screaming… that’s negative reinforcement. You took away the unpleasant chore, which reinforced the “tantrum” behavior.

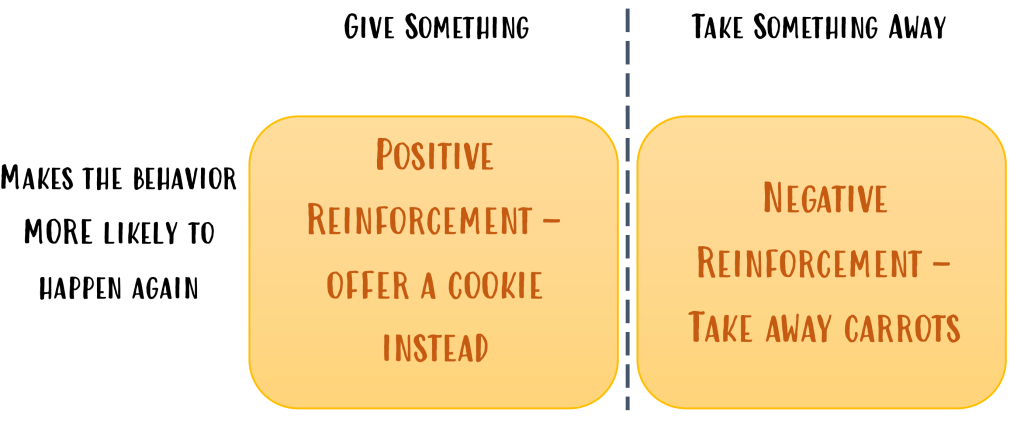

Let’s revisit our carrot scenario to see how positive and negative reinforcement would be used to actually make the negative behavior more likely. This time, let’s say your kiddo sees the carrots on their plate and yells “you know I don’t like carrots, mom! I’m NOT eating these.” Here’s how you might reinforce his yelling with positive and negative reinforcement:

Offer a cookie instead = give something good = positive reinforcement.

Take away carrots = taking away something unpleasant = negative reinforcement.

In this case, both positive reinforcement and negative reinforcement will make it more likely that your child yells at you again – and more likely that they won’t eat their carrots.

The two carrot examples above are also examples of how you can use positive reinforcement AND negative reinforcement at the same time. In the first example, giving a cookie as a reward will be reinforcing. Or letting your child off the hook for cleaning their dishes will be reinforcing. You can use one of these, or you can use both. Using them together will make the behavior even more likely – the reinforcement will be even stronger.

And that’s a wrap on positive and negative reinforcement. The most important thing to remember is this: Both positive reinforcement AND negative reinforcement are “good” – BOTH make a behavior more likely to occur again.

As always, I’d love to read your comments and questions – drop them below!

Disclaimer: I am a licensed mental health therapist, but I am not your therapist. The information in this article is for general informational purposes only. This article does not create a therapist-client relationship. If you need specific recommendations based on your individual circumstances, please consult with a mental health practitioner near you.